German | English

Reflections on the artistic journey of Hans-Jürgen „Hänner“ Schlieker, as seen through the „Geneva Collection“ of his works.

Hänner Schlieker has always been a presence in my life, not only as a beloved grandfather but also as an artist.

A typical work from the late 1960s hang on the wall of my first apartment in Berlin in 2000. Later, in my student home in the small town of Witten, it was joined by a large diptych, which accompanied me throughout my studies.

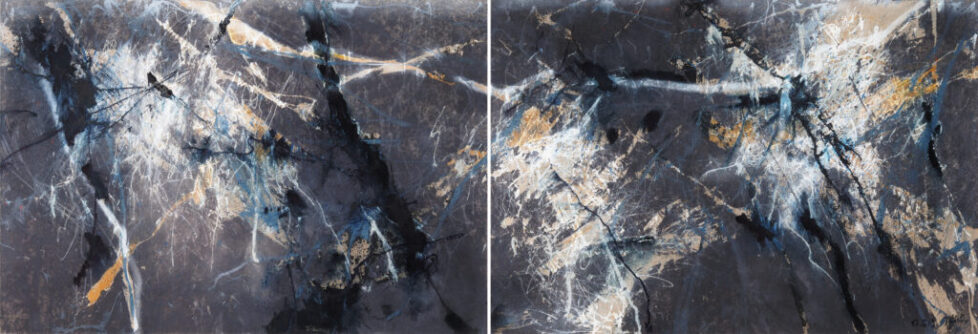

Over the years I collected more than 30 of his works. The core of the Geneva Collection is a diptych from 2003. It moved into my first apartment in Geneva in 2009, where it was within sight through countless sometimes inspired, sometimes arduous hours I spent writing my doctoral thesis.

After, it greeted visitors in the hallway of the first home my wife Miao and I moved in together, and where we welcomed our first daughter Luna.

Later, it would radiate across the beautiful, generous, open spaces of our Florissant apartment, where our second daughter Clea completed our family.

Today, the painting holds pride of place over the dining table in our home in Conches, a position of honor for one of Schlieker’s last works, completed shortly before his passing in 2004.

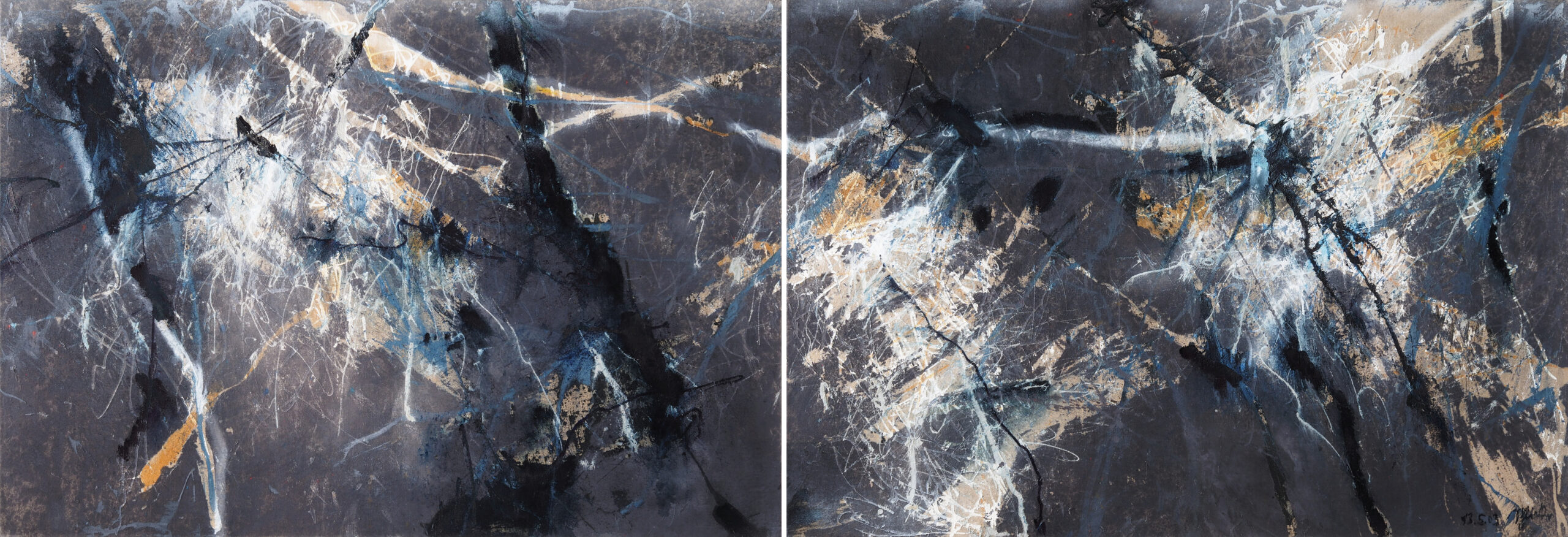

"13.5.03", 2003

As Schlieker paintings have always been in my life they speak to me in a deeply personal and likely subconscious way; they are silent companions, at times soothing, at times stimulating, and sometimes just there to reassure „this is home“.

However, when I started photographing and cataloging the works I collected over the years to commemorate his centenary, I started looking at them in a new and conscious way. Thus began a small journey of discovery into the world of an extraordinary artist.

1 Abstraction means liberation

Schlieker belongs to the second generation of abstract artists in Germany – one whose formative years unfolded in a land of barbarism and a world at war. In the post-war era, these artists pioneered a German style of abstract expressionism, in the art world also called „action painting“, „Tachism“, or „Informel“.

The style embraced non-objective, gestural, and spontaneous expression, freed from formal constraints, and focused on the tactile, material quality of color itself. Art was no longer subject to the aesthetic dictatorship of the Nazi regime, where all forms of artistic abstraction were banned and called “entartet”.

Painting should exist purely as painting: free from the illusion of perspective, unburdened by didactic content, unencumbered by untruths. An artwork should require no hidden mythology, and it should only reach completion in the mind of the viewer.

While Schlieker’s artistic expression remained primarily figurative until the late 1940s, the 1950s marked a decisive shift to abstraction. That decade was also one of significant personal transitions: he married, relocated from Hamburg to the beating industrial heart of Germany – the Ruhrgebiet – and welcomed his first and only child, Claudia, my mother.

It was during this transformative period that some of the earliest works in the Geneva collection were created, including a small, vibrant oil-on-canvas painting from 1958, and several works on paper produced between 1957 and 1959.

To understand Schlieker – and many artists of his generation – one must grasp the profound longing for liberation and new beginnings that defined their era.

But of course, none of this was evident to me as a young boy born over twenty years after his first foray into abstraction. My memories of him are primarily those of a man who created a whirlwind of creative chaos in his studio. Sometimes one could wade knee-deep through piles of colorful paper scraps. I also vividly remember a man who always had a funny, occasionally risqué, joke ready to lighten any stiff situation.

My grandfather’s deliberate yet humorous rejection of constraints and conventions extended far beyond brush and canvas – which, of course, we children thought was fantastic.

And yet, to attribute his work solely to the „Zeitgeist“ would be to tell only part of the story. A comparison between his 1957 painting „San Pol“, created in the small Costa Brava town just a couple of kilometers north of Barcelona, and his predominantly black-and-white work from 1959, likely painted on a winter day in his hometown of Bochum, highlights how profoundly his art was influenced by the environment and atmosphere in which it was conceived.

Critics would later frequently observe that Schlieker’s ability to perceive, internalize, and reinterpret nature and landscapes was a defining hallmark of his creative process.

2 Seeing, un-seeing, re-seeing

In the 1950s and early 1960s, the „Informel“ style captivated art audiences, challenging not only classic realism but also the formal constraints of geometric abstraction.

Yet, despite its immense popularity and historical significance and recognition as the „last international style“, the movement’s prominence already faded from the late 1960s. Known artists quietly abandoned or even explicitly rejected “Informel”, swiftly reorienting their approach as the movement unraveled.

But Schlieker – like Emil Schumacher and other pioneers of the movement – doubled down.

To understand why, Dieter Ronte, the long-time director of the Bonn Museum of Art, provides a clue in an essay where he describes Schlieker as a „visual basic researcher“. By that he meant that his goal was not to reject the object but to observe and distill its essential qualities or aspects.

Schlieker often cited Impressionists such as Lovis Corinth and Oskar Kokoschka as influences. To him, „Informel“ was less a radical departure from earlier ideas and more a powerful new instrument to achieve a goal he shared with these masters: to capture the intensity of human experience.

Grounding the genesis of Schlieker’s work in the intent to see, unsee, and re-see the world makes it more than just a product of its time. For artists who interpreted the “Informel” not just as „freedom from“ conventions and constraints, but as „freedom to“ engage with the outside world anew, it became a gateway to true innovation.

"Procida", 1978

The visual basic researcher in him weathered the crisis of the movement by re-immersing himself in the real world – nature and landscapes in particular – re-confronting his subject, re-discovering its essence, and thus recalibrating his approach. He later reflected about this time as „inner necessity to renew my way of painting, to escape the risk of routine“.

Comparing two works on paper in the collection from this time – “Garmisch 77” (p. 38) and “Procida” (p. 39) – to the before discussed works from the 1950s illustrates this evolution. If the black and white work from 1959 could most aptly be described as abstract interpretation of a winter landscape, “Garmisch 77” approaches the theme from the opposite end, resulting in what could be called winter landscape infused abstraction.

Similarly, while the work on paper created in San Pol could be described as abstract interpretation of a Mediterranean setting, the work created on Procida in the late 1970s, could instead be circumscribed as abstraction suffused with Mediterranean summer light.

It was rare for my grandfather and me to talk about his art. Yet I vividly remember one occasion when he insisted that one cannot master the „Informel“ without first mastering „Realism“ in all its facets.

At the time, I understood his stance as a comment on the craft of painting – something along the lines of, „You need to earn the right to play with color the way I do“ (possibly delivered with a wink and smile as we compared our childhood doodles on his studio wall with his canvases).

Today, I ask myself if his words were less about the „doing“ and more about the „seeing“ – Regardless, the importance of the objective world as a source of inspiration, a starting point, and a driving force for Schlieker cannot be overstated.

3 A Kind of Artistic Score

When my sister and I were teenagers, my grandfather once invited us to Art Cologne, a big German art fair. There, he would point to various artworks, confidently naming their creator from just a glance, then sending us off to check if he was correct. We were quite impressed – he was almost always right.

From that day forward, I remember looking at him with a new kind of admiration. Before, I had somewhat thought of his painting as more of an elaborate craft; only then I realized there was much more to it.

In fact, Schlieker was a teacher throughout his life. Just as his encounters with nature shaped his perception, working with students offered him the opportunity to step back and reflect on his craft. His students later remembered him as unrelenting in exposing flaws and disproportions, rigorously questioning the visual and, in doing so, opening their eyes – and his own – to new perspectives.

His recurrent immersion in “visual basic research” on the one hand, and the classroom on the other, set important impulses in the evolution of his art.

Irrespective of his pivot to abstraction in the 1950s, intellectual composition dominated emotional expression in his approach until the early 1970s. Across his works, a primacy of formality – a kind of artistic score – still guided his hand.

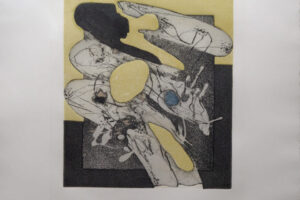

That primacy of formality appeared, for instance, in the utilization of geometric shapes in some of his compositions, as seen in the collection in a work from 1959/60, a 1968 series of etchings, and a painting from 1969.

In his later years, Schlieker added a playful twist to this approach by cutting out fragments from earlier works, mounting them onto a new canvas, and then layering color on top. See, for instance, the two collages from 1998 and 2002.

Formality was also evident in organic forms sitting firmly within the physical frame, as in two gouaches from 1960 and 1961. In later works, the action cut across and beyond the frame, with centers that felt positioned outside.

The artistic rationale for using constructive counter-elements in a gestural painting reflects an idea that is both simple and philosophical: a concept gains clarity and meaning in relation to its opposite. The counter-element injects a tension between process and structure, chance and control, even emotion and calculation, and that way helps transform seemingly arbitrary gestures into a cohesive image.

Much like inflating a balloon, the aim is to build tension without allowing the structure to collapse. In that sense, getting to visual clarity and quality requires not only to act but also to know intuitively when to stop.

4 Clarity on the Edge of Chaos

While the foundational concept of using constructive counter-elements endured, its realization shifted profoundly in the 70s. Geometric forms and other formal elements no longer seemed necessary to create the tension that transforms the application of color into a painting.

Although this was just the period when Schlieker re-immersed himself in nature and landscapes, it is too simplistic to suggest that organic elements replaced geometric ones. Something more profound was at play.

His aim no longer was to capture the moment but to capture a process or movement – the relentless, merciless interplay of emergence and entropy, the antagonistic forces of becoming and unraveling that define every aspect of life.

Recorded by Christoph Böll’s camera, which left an invaluable record of this process, we see how, in one moment, small, carefully drawn details are washed away while, in another, spontaneous bursts of color develop into central forms.

Genesis of a Painting

The focused, restless oscillation between chaos and order not just aims to „see“, it aims to „be“, thus setting new boundaries from which visual clarity and intensity emerged.

It was a leap which would define the artistic approach for which Schlieker became known and recognized – a unique stance beyond prevailing trends and the at times polarized positions of figurative versus abstract art.

"Untitled", 1999

Reflecting on this shift through the lens of a social scientist, it aligns closely with a well-known paradigm in complexity theory called „the edge of chaos.“

In a system of perfect internal order, like a crystal, no further change is possible. At the opposite, in a highly chaotic system like boiling liquid, there is too little structure left to sustain meaningful change. Evolving living systems exist between these extremes – precisely, at the edge of chaos – where they maintain enough order to function while also remaining flexible enough to adapt and transform.

From the 1980s, Schlieker’s paintings truly began to explore this space. The oil-on-canvas paintings in the collection from 1985, 2002, and the diptych from 2003 are examples of the fascinating visual worlds that emerged from here.

5 Etching is a Sacred Act

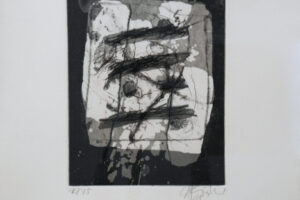

An extensive body of etching works – a printmaking technique in which designs are incised into metal plates with acid, then inked and pressed onto paper to produce intricate prints –perfectly epitomizes Schlieker’s approach.

A notable example is a print series from 1997, named after the North Sea Island of Sylt, with three works included in the collection.

As with these works, most „etchings“ begin with a bold, direct intervention on the surface of the printing plate, using an array of unconventional tools – metal brushes, drills, scrapers, screws, nails, chisels, and even pastry wheels. The fine grooves collect the ink, which is then transferred onto paper.

But this is only the start. It follows the etching process that enhances the image with bold, contrasting tonal areas, and that gives these works their name. Schlieker would document stages of the process in separate prints, as exemplified by two pairs of works from 1999.

Further refinements emerge through color variations, plate combinations, and changes in the printing process. This evolution is vividly exemplified by a vibrant, joyful series of four prints from the late 1990s. A closer look at these works reveals numerous plates and plate combinations Schlieker used to create them.

The etching process was documented in another episode of a ten-part series filmed by Christoph Böll during the final years of Schlieker’s life. Titled „Etching is a Sacred Act“, it provides a captivating insight into the philosophy and craftsmanship behind the creation of these unique works.

Etching is a Sacred Act

Seeing, un-seeing, and re-seeing the works of my grandfather awakened in me a renewed sense of wonder.

I discovered a legacy rooted not only in the works themselves but in a powerful idea: the pursuit of perceiving and performing the raw yet poetic forces of life.