German | English

When my sister and I were teenagers, my grandfather once invited us to Art Cologne, a big German art fair. There, he would point to various artworks, confidently naming their creator from just a glance, then sending us off to check if he was correct. We were quite impressed – he was almost always right.

From that day forward, I remember looking at him with a new kind of admiration. Before, I had somewhat thought of his painting as more of an elaborate hobby; now I realized it was a craft he mastered in theory and practice.

In fact, Schlieker was a teacher throughout his life. Just as his encounters with nature shaped his perception, working with students offered him the opportunity to step back and reflect on his craft. His students later remembered him as unrelenting in exposing flaws and disproportions, rigorously questioning the visual and, in doing so, opening their eyes – and his own – to new perspectives.

His recurrent immersion in “visual basic research” on the one hand, and the classroom on the other, set important impulses in the evolution of his art.

Irrespective of his pivot to abstraction in the 1950s, intellectual composition dominated emotional expression in his approach until the early 1970s. Across his works, a primacy of formality – a kind of artistic score – still guided his hand.

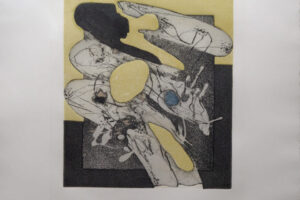

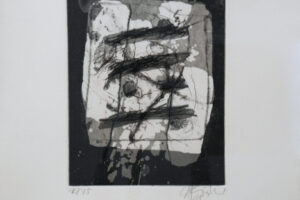

That primacy of formality appeared, for instance, in the utilization of geometric shapes in some of his compositions, as seen in the collection in a work from 1959/60, a 1968 series of etchings, and a painting from 1969.

In his later years, Schlieker added a playful twist to this approach by cutting out fragments from earlier works, mounting them onto a new canvas, and then layering color on top. See, for instance, the two collages from 1998 and 2002.

Formality was also evident in organic forms sitting firmly within the physical frame, as in two gouaches from 1960 and 1961. In later works, the action cut across and beyond the frame, with centers that felt positioned outside.

The artistic rationale for using constructive counter-elements in a gestural painting reflects an idea that is both simple and philosophical: a concept gains clarity and meaning in relation to its opposite. The counter-element injects a tension between process and structure, chance and control, even emotion and calculation, and that way helps transform seemingly arbitrary gestures into a cohesive image.

Much like inflating a balloon, the aim is to build tension without allowing the structure to collapse. In that sense, getting to visual clarity and quality requires not only to act but also to know intuitively when to stop.